-

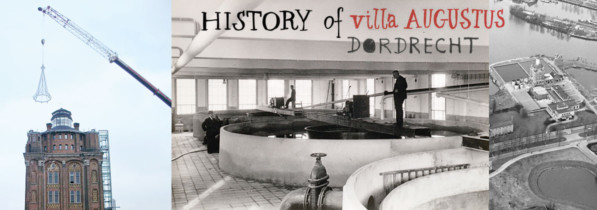

Aerial photograph 1930

Aerial photograph 1930

-

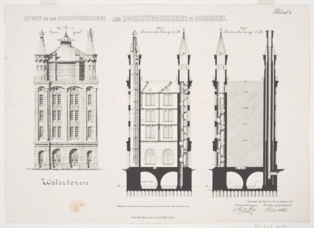

Source: Dordrecht regional archives

Source: Dordrecht regional archives

-

From: De watertorens van Dordrecht en Dubbeldam

From: De watertorens van Dordrecht en Dubbeldam

-

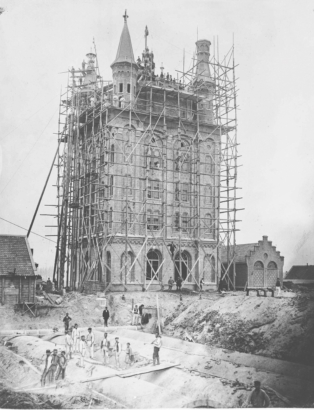

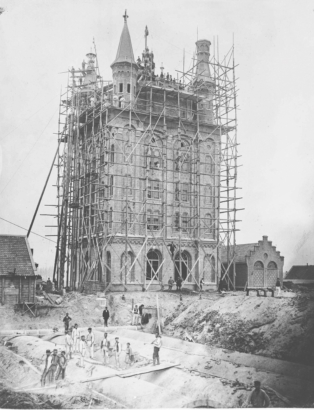

The water tower under construction, 1882

The water tower under construction, 1882

-

The water tower during renovation in 2006

The water tower during renovation in 2006

Aerial photograph 1930

Aerial photograph 1930

The photograph

One day in 2003, the photograph appealed to the imagination of a number of entrepreneurial people who saw it in the town hall. The water tower was vacant, awaiting a new purpose. For example, as a hotel: imagine sleeping in a tower where water used to be stored. The surrounding site, which – as can be seen in the photograph – used to be water, could be opened up again. The Vlij River could be extended, restoring its old course. The new pump building next to the tower, not visible on the photograph because it was not built until 1942, would be an ideal location for a restaurant and a market. (FB)

Source: Dordrecht regional archives

Source: Dordrecht regional archives

A second life for the water tower

The water tower in the Oranjelaan, on the banks of the Wantij river, no longer weeps. Water no longer runs from the leak trap under the reservoir, through the round windows and down the brick walls. The only water flowing on the fourth floor of this national monument now is in the luxury bathrooms of the hotel rooms.

Thanks to the innovative ideas of conservationists and hospitality sector entrepreneurs, the tower on the Wantij escaped the demolition hammer. It was completely renovated and started a new life. The tower has become a part of a unique Dutch garden of delights, with a restaurant, garden, hothouses, and the water tower that was re-born as a hotel: Villa Augustus.

From: De watertorens van Dordrecht en Dubbeldam

From: De watertorens van Dordrecht en Dubbeldam

A water tower on the Wantij

On 31 January 1881, J.A. van der Kloes, Director of Public Works, and consulting engineer A.G. de Geus, presented their design for a ‘high-pressure water mains supply in Dordrecht’. The project comprised the construction of a complex along the river, including clarification ponds and filtering basins to purify the water before it was pumped into clean-water basements. Amidst these water basins, the drawings showed a beautiful castle-like tower with a water reservoir: Dordrecht water tower.

The construction costs were estimated at 475,000 guilders. The operating costs would be 41,120 guilders a year if the people of Dordrecht used 1,000 cubic metres per day, and 45,100 guilders if they used 2,000 cubic metres per day. This would be recovered by charging the town’s households rent for the mains water supply. Back then too, the socialist idea that the strongest shoulders should carry the heaviest burden applied. The most important question the town leaders had to answer was ‘where do we get the drinking water to be supplied by the water tower’?

Chemical research carried out in 1873 by Dr. G. Post had shown that the cleanest water was in the Merwede river, just beyond the Kop van de Staart, a harbour area adjoining the old town centre. Van der Kloes and De Geus advised the municipal council to construct a water inlet and build the water tower at this location.

However, the council was not in favour of building there, as the area was still poorly accessible. Moreover, they considered the water from the Biesbosch, which flowed along the Wantij to the town, sufficiently clean. On 15 March 1881, the council decided to build and operate the high-pressure water mains supply on the Wantij. Dordrecht would be drinking water from the Biesbosch, as this part of the Wantij was called at the time.

The water tower under construction, 1882

The water tower under construction, 1882

A monumental water plant

Van der Kloes himself designed the Dordrecht water tower. In later years, he would become a teacher at the Delft Polytechnic, the predecessor of the Technical University. His tower on the Wantij is still highly commended by architects and has been declared a national monument. Construction started in 1881 and the tower was finished in 1882. The Director of Public Works had designed a tower 33 metres high. It was a squarely-built structure with four octagonal towers surrounding a large, round water reservoir. In two of the towers, there were spiral staircases between the staff residences and the reservoir. One tower contained the chimney for the smoke from the steam engines pumping up the water from the basements to the reservoir. The fourth tower was intended as an outlet for the water if the pressure inside the reservoir became too high. The towers were to disappear in 1938, when the reservoir was raised by means of a metal shaft.

The tower’s outline looks rather like a castle. Underneath the tower are the clean-water basements. On ground level were the pumps. The floors above contained five apartments for the operators. Above these was the leak trap, just below the reservoir at the top. The round windows in the leak trap served as outlets for the water, if the reservoir became too full. After the Oranjelaan was built in 1908 and 1909, passers-by would look at the water trickling down the brick walls and say “the water tower is weeping”.

In 1882, the round iron reservoir could hold some 500 cubic metres of water. Together with the ponds, the tower formed a water factory in which the water from the Wantij was purified before being pumped into the mains network. The working conditions during the construction of the factory in 1881 and 1882 were tough. Because of the high water level in the rivers, the building site sank while it was being raised. As a result, the clarification ponds could not be dug to the required depth and they soon proved to be too small.

In the spring of 1883, Van der Kloes and De Geus were criticized by a special committee. Although the construction eventually cost 535,000 guilders – 60,000 guilders over budget – the committee reproached them for being too thrifty. This may have been why the mains water supply had insufficient capacity. Furthermore, the water was allegedly not clean enough. The local newspaper, the Dordrechtsche Courant, published special supplements discussing the affair at length. In an attempt to defend himself, Van der Kloes referred to the bad weather conditions and the time pressure. Despite all the delays, on 1 November 1883, officially approved pure water flowed from the water tower to homes in Dordrecht. Dordrecht now had its own drinking water company. The inscription on the side wall of the water tower recalls this memorable moment:

The enemy, often the terror of the Dutch lowlands,

Has entered this house.

And it leaves again, as a good friend of the sick and the healthy,

Towards Dordrecht

(AO)

The water tower during renovation in 2006

The water tower during renovation in 2006

And more…

De watertorens van Dordrecht en Dubbeldam (in Dutch) by André Oerlemans, in the series Verhalen van Dordrecht is on sale in the Market. This book is published by Stichting Historisch Platform Dordrecht & Stichting Illustre Dordracum.

- € 3,95

Also available in the market: the film Dit is Villa Augustus and the book De tuin van Augustus, which tell the stories of Villa Augustus and its garden (both in Dutch).

–

Text with thanks to Frits Baarda (FB) and André Oerlemans (AO).